East is East

Is there a common ground for the twain to meet? The sixth was a good BCE century. Thales lived into it as did Laozi of China. Siddhartha Gautama, affectionately known as the Buddha, was born in it. So inquiry started at the same time, first in the West with the pre-Socratics, then the insight seekers of the East. There was, however, a major difference in the form the inquiry took. In the West it was exoteric, of and concerning the outer, shared reality that all could observe. Exoteric (scientific) knowledge may be difficult to obtain, but it is obtainable for the price of an effort and subject to public confirmation or falsification. If you want to know how many teeth horses have, open horses' mouths and count.

Science and most scholarship is the pursuit of evidence-based exoteric knowledge. Pseudoscience/pseudoscholarship is not. Exoteric knowledge claims are by degree true or false, and the true has to be separated from the false—a difficult, never ending, yet to some degree or another, a possible task.

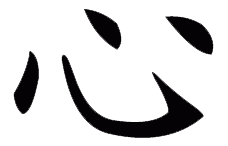

What sort of knowledge does religion seek? If religion differs from science, it must pursue something other that outer knowledge, and that leaves 'inner' knowledge or insight that is not publicly verifiable. The usually given opposite of English 'exoteric' is 'esoteric', but that word has unfortunate connotations and so will be replaced by 'inner' as exoteric can be thought of as 'outer'. Let's define 'inner' as attentive inquiry into that mind which is private, within the skin, into that which is immediately, continuously present; those thoughts, feelings, and perceptions that play out within the mind in the ever present and are not directly experienced or observable by others. This inquiry is into the subjective, existential nature of being, of aliveness, of the human condition, as a private seeing in the here and now through 'mindfulness' (as apposed to 'thoughtfulness') of it all.

This awareness of the all that is also the one, is prior to thought-consciousness forming dualistic concepts about it and thinking about the concepts. What can be observed can be turned into concepts, but that becomes part of scientific inquiry. Religious inquiry focuses on the present to the exclusion of thoughts about the past, future, or even the present. There is nothing necessarily wrong about such thoughts, but they are not religious (inner) in any sense. Awareness of the present is the what-is—to be awake and not asleep, to the living, unfolding, 'eternal now' that is moment by moment being. This awareness includes others, their suffering, and so empathy, caring, and compassion naturally follow. Compassion is of religion and we humans need it if we are to survive.

Any individual's inner claims can be verified, but not publicly. Claims can be voiced and can then be given consideration by other individuals who are also on the religious quest to further their inner inquiry. If they test and find the claims to be as the words hint at, then claims are at best confirmed by one individual for that one individual. This is not unlike science other than claims cannot be publicly confirmed directly and so no religious claims are or can be held by a group to be asserted as belief by a group. This means that organized religion is an impossibility (though, sadly, pseudoreligion is ever organized). The inner quest or inquiry involves experiments in self-directed neuroplasticity called meditation or mindfulness in the East.

Unfortunately 'meditation' can refer to a belief system such as surrounds a practice, and more often, even in the East, it does. Practices are one thing, beliefs surrounding them are another. So there is 'Transcendental Meditation' which entails some practice but is largely defined by its guru worship and overarching beliefs. The only alternative is individual experimentation and inquiry into mindfulness, which alone merits consideration (no absurdities allowed or implied), and that as such is the religious quest.

All exoteric religion in the West is false, which leaves only a few 'mystics' to consider. Meister Eckhart, 13th century theologian and mystic, said, “Why dost thou prate of God? Whatever thou sayest of Him is untrue.” If anything one can possibly say is false, then anything one can possibly think is also untrue, so with no possibility of 'true dogma', only 'mysticism' for mysterians remains. A possibility of a transcendent 'something' cannot be meaningfully spoke of, though inner existential inquiry remains possible. To even think of 'enlightenment' is to go astray. But whatever you do, STOP PRATING! If you must consider the transcendent and the word 'god' comes up, consider the 'transcendent' as a matter of taste. Admit it is not one of truth. Perhaps as dogs cannot understand Calculus, humans may not be able to understand the overarching reality of the universe. But the 'that' of which you imagine cannot be spoken of, nor thought about, so say nothing!

All exoteric religion in the East, and there is plenty of it, is also necessarily false. Explanatory fictions, like reincarnation, karma, or qigong, can be claimed to be fact, but cannot be inwardly verified, and attempts to prove, using reason and evidence, are unconvincing to all who do not already believe. Claims for reincarnation are exoteric and are best to be examined critically by science. And if compelling evidence comes up short, then consider the concept dubious. Concepts, like rebirth, souls, gods...have nothing to do with religion, but are all claims for critical exoteric consideration. Beliefs that are not reality-based, tell us nothing about the world.

What the East has excelled in, by comparison with the West, is in inner inquiry which takes place within an inquiring mind whose subsequent claims or teachings, if any, may be considered, but never believed in. As religious scholar Huston Smith (born and raised in China) noted, all religions fall into two categories, 'religions of creed' and 'religions of quest'. But since only individuals can undergo a quest, all organized religions are of historical and anthropological interest only. That some organized religions arose in the name of some individuals (Laozi, Buddha....) is not something that need be held against them. People like Laozi were functioning in a religious mode, living a religious life, but their followers, qua followers, were not. The inner quest has generated some literature of interest: The Tao Te Ching, Diamond Sutra, Tibetan Book of the Great Liberation, Platform Sutra, and the teachings of Huang-po, but if a single word be understood, nothing is to be believed.

This leaves the rest of the set of all possible knowledge claims. Science has its legion of pseudoscientists and religion has its even larger number of questionable claimants. So many that for most free thinkers the term 'pseudo-religion' seems repetitive, and 'true religion' sounds oxymoronic. But perhaps this is because most free thinkers are of the West and think of 'JudeoChristianIslamic' when and if they think of religion at all. The general principle advocated here is that all exoteric religious claims are false ('exoteric religion' being oxymoronic) and esoteric claims tell us nothing of this world, our shared conceptual outer world. Extraordinary esoteric claims are false as they generally posit another world of alleged existence, undetectable and untestable. They tell us much about the nonexistent, and nothing about the existent. Is the real world so uninteresting that we prefer other worldly beliefs to it?

The claim that Zeus exists is an exoteric claim for which evidence might be expected to exist. Claims that Zeus throws and thereby causes lightening bolts is a claim for science to consider and reject due to the total lack of compelling reason and evidence to support it. All other claims about things outside a claimant's skull are not religious in nature, and so subject to public falsifiability. Claims about the intraskullular world are inner, possibly religious (as distinct from pseudoreligious), and not directly within the purview of science (though machines with wires can provide indirect evidence and of course should).

To suggest that the East can be concilient with Western free inquiry, here's a bit from Buddha's 'Charter of Free Inquiry' as spoken to a village of the Kalama people who had been inundated by wandering "holy men" claiming incompatible certitudes and bad mouthing one another. Buddha said to them, "It is proper for you, Kalamas, to doubt, to be uncertain. Uncertainty has arisen in you about that which is doubtful. Come, Kalamas. Do not believe what you have merely heard repeated; nor upon tradition; nor upon rumor; nor upon what some may call scripture; nor upon surmise; nor upon an axiom; nor upon specious reasoning; nor upon what is claimed true by faith alone; nor upon any authority whom others call, 'Teacher!' Kalamas, when you yourselves know because you have tested and observed for yourselves: 'These things are bad; these things are blamable; these things are questionable; these things lead to harm and ill,' then abandon them... Do not accept anything by mere tradition... Do not accept anything just because it accords with your scriptures... Do not accept anything merely because it agrees with your preconceived notions... But when you know for yourselves those things that are moral, those things that are blameless, those things that are to be praised, performed, and undertaken, then live and act accordingly." Of course, understanding even a single word of the above means you shouldn't 'believe' anything Buddha is alleged to have said either.

So free inquiry is of both East and West. The main difference is that the worst of faith-belief has been in the West where many centuries of 'religious' trench warfare have been carried out. Although, as noted, the West is not yet a 'culture of inquiry' some within it have come as close as the ancient Greeks, and science, as some few are aware, has progressed far beyond all that has been seen before.

Organized science did not arise in the East as inquiry was far more inner there, or in Western jargon, Eastern inquiry was mostly existential or therapeutic in focus, as inquiry into dysfunction, into suffering and the ending of suffering. Inner inquiry involves individuals mindfully looking at: Being, their own and others, the One and the All, the human condition, the coming of death—and the religious inquiry can, of course, also be thought about, but that becomes religious philosophy. It is not 'either or', so try 'and both'.