The Woman Who Stood Up

In the remotest of mountain valleys in ancient China lived a people so isolated that no one in memory had ever left and no one from the outside had ever ventured in. The Emperor of the valley ruled all he surveyed. Knowing no rivals within, he had no enemies from without, and so he encouraged the forgetting of the world outside the paradisaical valley. The stories his Priests told soon changed. For several decades the people prospered, but then the pestilence came. The Emperor alone of the royal house was spared, confirming his divine being. The Royal Guards pampered him. His Priests extolled his magnificence to such commoners as the plague had spared. As the Priests intoned, those who survived were spared by the Emperor to serve Him and his Priesthood.

The court vassals who bowed the lowest pleased the Emperor most, advanced the highest, and lived the longest. Those who displeased the Emperor soon disappeared under escort by the Royal Guards to what came to be thought of as a better life. The bowing soon became so low that all within the Emperor's sight crawled, never rose, and in short time all in the valley came to crawl as well. It was dangerous to stand even in private as if one's own child saw you, all would soon know and the offense was inexcusable. Crawling came natural to children and they never learned to get about any different way. It was dangerous for the elders to think about or even remember ever having stood up, and within a generation the possibility was forgot. The Emperor, who alone could stand, in due course passed on to the Higher Abode where he walks to this day. His Priests assured the people that their Emperor would come back provided they continued to please him in the manner the priests taught them. Chief among the ways being the taking care of his Chosen Ones.

Generations passed. All structures were rebuilt with low doors and ceilings, all except the Emperor's Chamber, now the Holy of Holies. The Emperor who had alone stood up, who now walked among the walking gods, wanted all his followers to stand as well, said His Priests, and those who proved themselves deserving of going to His Abode in the next life would surely walk with their Emperor. The idea of standing thus existed, but it was not of, nor for, this pestilent world. Only the demon haunted possessed by Evil would think to stand in this life.

Ling was but a young girl when she wondered about the parts behind the knee pads. Why did the people have them? She came to develop a fascination with the big wading birds. She marveled that they walked on but two legs. The priests helpfully explained that because their knees bent backwards, no bird could walk in the proper way. Only humans, of all the animals with hair, could raise up on their knees and use their front legs to do work in service to the Emperor and His Priests. But Ling could not understand and came to regard herself as dense. Yet still she wondered at many things and learned to say nothing.

The hands she walked on had many bones and moved in useful ways. The feet too had many bones, far more than needed to be dragged behind the knees. She realized that the below the knee part, as the priests taught, did help steady us to raise upon the knees as well as craw upon them. Yet the complexity of the feet, so similar to the hands, seemed excessive. And why the pain on crawling? Other animals did not seem to move in pain. Again the priests explained that as the First Woman had once thought to stand up in this life, she and all her spawn had to be punished. Still Ling did not understand, so she just came to smile when the priests talked.

She did not smile at Heron, but watched him intensely as he gracefully moved one leg then the other, his feet serving an obvious purpose. She would dream of doing the same, then awake in terror that such evil could grip her mind. If the priests knew, they would know what had to be done. Sometimes she would awake and feel her lower limbs tingle as if from exertion; they became more flexible. The years passed and Ling got used to her aberrant urges. She watched the priests but smiled less. What did they know? What did anyone know and how did they know it?

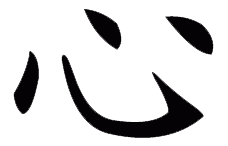

One day Ling was sitting under a great tree. A demon appeared tempting her to do what only the gods could do. How monstrous the thought that she could stand up and become god-like. The immensity of her evil ego overwhelmed her as the demon laughed incessantly. Then a great calm washed over her. There was nothing real in thought. There was a light movement of the air, a butterfly flapped it's wings, flies buzzed softly in the distance, unseen a bird chirped, light filtered down to the forest floor—only reality, the what-is remained. The demon and his laughing grin were gone. Ling was standing up.

Ling's mind was utterly still yet awake as it had never been. She felt normal for the first time and knew without a single thought arising that she had attained nothing by standing, had achieved nothing. She was standing like a piece of uncarved wood arising from the forest floor. Nothing had been added, only something taken away. Gone was the beclouding fog of belief. As Ling walked out of the forest upright, the first person to see her did not kill her on sight and soon realized she was utterly human. There was cause for some hope that the suffering of others could also pass away, that they too could become ordinary. When none believed the Priests, perhaps they too, the believers and their priests, would pass away and become ordinary.